Nurturing Biodiversity

North American hardwood forests are home to 85 species of mammals, 130 species of fish, about 32,000 species of insects, and 300 species of birds, all of which rely on hardwood forests for their survival. Add to this about 40 species of plants and trees, and 45 species of fungi.

Conserving Soil and Water

The extensive and interwoven root systems in hardwood forests help prevent soil erosion and retain moisture, reducing the risk of floods and maintaining water quality. These ecosystems are also natural filters, absorbing pollutants and filtering water before it joins underground water systems or is released as vapor back into the atmosphere by trees and plants through transpiration.

Providing Infinitely Renewable Resources

Hardwoods are some of our most precious and coveted materials for fine furniture and millwork. The trees from which they come are an infinitely renewable resource when harvested sustainably. Responsible forest management practices include harvesting strategies that mimic a forest’s natural cycle of destruction – fires, insect damage – and regeneration, maintaining the same mix of species and the landscape in which they thrive. Properly managing forests ensures that we’ll have an ample supply of hardwoods for generations to come.

Producing Sustainable Building Materials

Because hardwood forests are programmed by nature to continually renew themselves, the lumber we harvest from them is – by nature – the most sustainable building material on the planet. Hardwoods are also one of the most versatile and workable, and capable of providing a range of aesthetics for every taste and trend. The use of hardwoods allows us to reduce our reliance on non-renewable materials, such as concrete, steel or plastics, which have much higher carbon footprints.

Purifying the Air

Hardwood trees absorb C02 and other greenhouse gases and release oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis. Trees also trap and filter airborne pollutants, reducing the concentration of harmful substances in the atmosphere.

Sequestering Carbon

Hardwood trees absorb more CO2 than other types of trees and plants. The captured carbon becomes part of the wood mass as the tree grows and remains sequestered until the wood burns or decays, which can be anything from years to centuries. And hardwood trees are harvested just before they die, as the carbon is sequestered at its peak. As a “carbon sink,” hardwoods are helping mitigate climate change by reducing the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Carbon and the Carbon Cycle

Carbon – “C” on the periodic table – is the sixth most abundant element in the universe, but only makes up 0.025 percent of the earth’s crust. It’s a solid that takes on different forms, the purest being diamonds, graphite (pencil lead) and carbon black (a sooty material found in pigments for inks, paints and plastics, and as filler in rubber tires).

Carbon is unique in that it bonds very easily with other elements, forming more compounds than all the other elements combined. When it meets two atoms of oxygen – “O” on the periodic table – it creates carbon dioxide, or CO2.

This unique bonding ability is why carbon is also the chemical backbone of all life on Earth. Humans are 18% carbon by weight, with carbon as a major component of our body’s sugars, proteins, fats, DNA, muscle tissue and bone. Hardwood trees are 50% naturally captured carbon by weight. That’s the highest carbon content of any living thing on earth.

CO2 vs. Carbon

When people say “carbon” in the context of sustainability or climate change they’re often talking about CO2. But CO2 and carbon are not the same thing.

CO2 is a colorless and odorless gas emitted when mammals, birds and reptiles exhale, and when plants and animals decompose. It’s also generated when we burn these formerly living things, in the form of fossil fuels. It’s a greenhouse gas, which means that with other GHGs it acts as a blanket that keeps heat from escaping the atmosphere, preventing the planet from freezing over. This is why a balanced level of CO2 is essential for sustaining life. But over the last 200 years this balance has been thrown off kilter.

Remember that there’s only a fixed amount of carbon in the universe. We’re not “generating” new carbon with these activities, we’re just releasing it from where it had been stored. Which brings us to the “carbon cycle.”

The Natural Carbon Cycle

Most of Earth’s carbon is stored in rocks, soil, and sediments. The rest is in the ocean, atmosphere, and living organisms. These are the reservoirs, or sinks, through which carbon cycles over hours, months, years, and millennia.

In the natural world, this stored carbon is released into the atmosphere through volcanic activity, forest and prairie fires, outgassing from warming oceans, the respiration of living organisms and decomposition of organic matter. Before the industrial revolution, the Earth’s forests and oceans were able to absorb this atmospheric CO2 keeping the cycle in balance, but they’re not able to keep up with the extra manmade emissions.

Healthy Forests to the Rescue…With Man’s Help

Healthy forests are bearing the brunt of scrubbing excessive concentrations of C02 from the air. Trees naturally capture atmospheric C02, use the carbon to create sugars for their growth, and release the oxygen…running on nothing but sunlight and water, through photosynthesis. That naturally captured carbon is sequestered until that wood burns or decomposes, making wood nature’s most perfect carbon capture and storage mechanism.

Globally, forests capture and store about 30% of the carbon dioxide that is released by human activities each year, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), more than any other capture mechanism.

To continue doing this, forests need man’s help. We’ve been putting out fires and killing tree-damaging insects to protect the homes, cabins and recreational areas we’ve built in forests. But this overprotection has come at a cost.

Fires and insect damage are part of forests’ natural cycle of renewal. Fires take down standing dead timber, remove deadwood fuel and undergrowth, and even help some trees germinate. Healthy trees are scorched but left standing, and the newly cleared floor and canopy are soon regenerated. Insects typically target older dying trees, leaving more room for younger trees to thrive.

Overprotecting these forests has led to an increase of deadwood and undergrowth – the fuel on which the flames feed – so when fires do break out they burn much hotter than nature can handle. Healthy trees are killed, and in some cases extreme temperatures literally sterilize the soil, preventing natural regeneration for years or decades.

In managed forests, companies are careful to only harvest trees that are fully mature, at the point where they are starting to die naturally. Their ability to capture CO2 is diminishing, they’re becoming more prone to disease, and their yield of useable wood is at its maximum. Like a fire, managed forestry opens up the floor and canopy to allow natural regeneration, supplemented by replanting programs when necessary, that honor the natural biodiversity of that particular forest.

There are More Hardwood Forests Now Than 100 Years Ago

Managing these critical ecosystems makes for a great sustainability story, of course, but the hardwood lumber industry was already fully behind these efforts long before anyone had even heard the term “climate change.” Why? Because it’s just good business. The importance of protecting forests to ensure access to quality wood into the future has been understood since the early 18th century, express in this simple mantra: “Never harvest more timber than the forest can regenerate.”

In other words, it’s never a good idea to kill your golden goose.

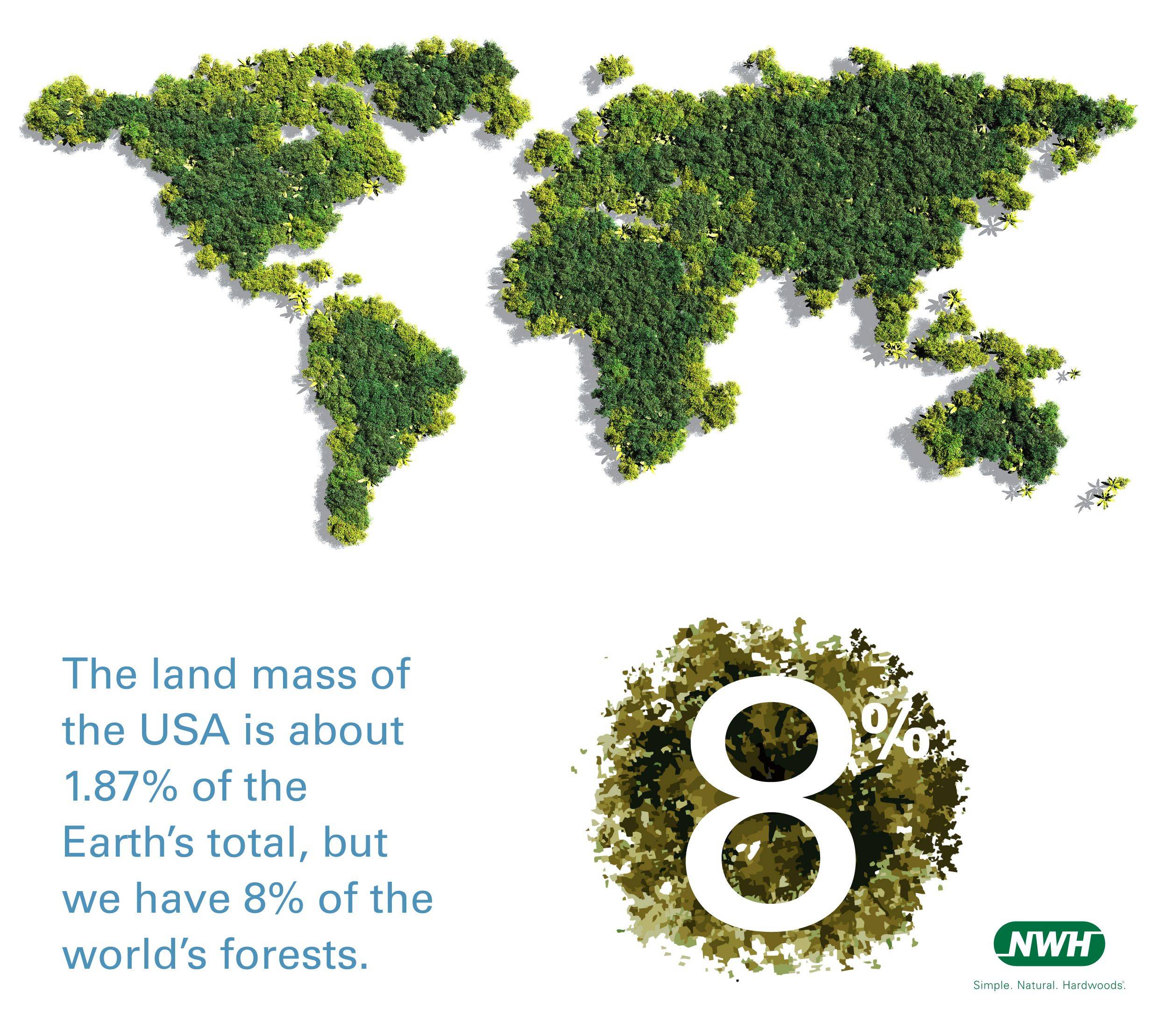

The land mass of the USA is about 1.87% of the Earth’s total, but we have 8% of the world’s forests. While significant areas of forests were cleared for agriculture as our country grew, we actually have more trees now than we did 100 years ago. Thanks to managed forestry, forest growth has been outpacing harvests since 1940. Between 1990 and 2020, total forest area in the U.S. increased by 18 million acres. That’s the equivalent of 1,200 NFL football fields…every day.

This wouldn’t be the case without hardwood lumber companies protecting this important resource. The health of this global industry is directly tied to the health of our forests, and our planet. As we unleash the potential of this beautiful and unique material, the benefits will only multiply.

– Kenn Busch, Material Intelligence

Share This Post!