When asked what the biggest misconception is about his job as Timber Resource Manager for Northwest Hardwoods (NWH) in northwest Pennsylvania, Christopher Guth laughs and says quickly, “When I say I’m a forester, people think I mean forest ranger. They think I’m up in a fire tower looking for smoke.”

“People don’t think of a forester as working within the timber industry.”

What is an industrial forester?

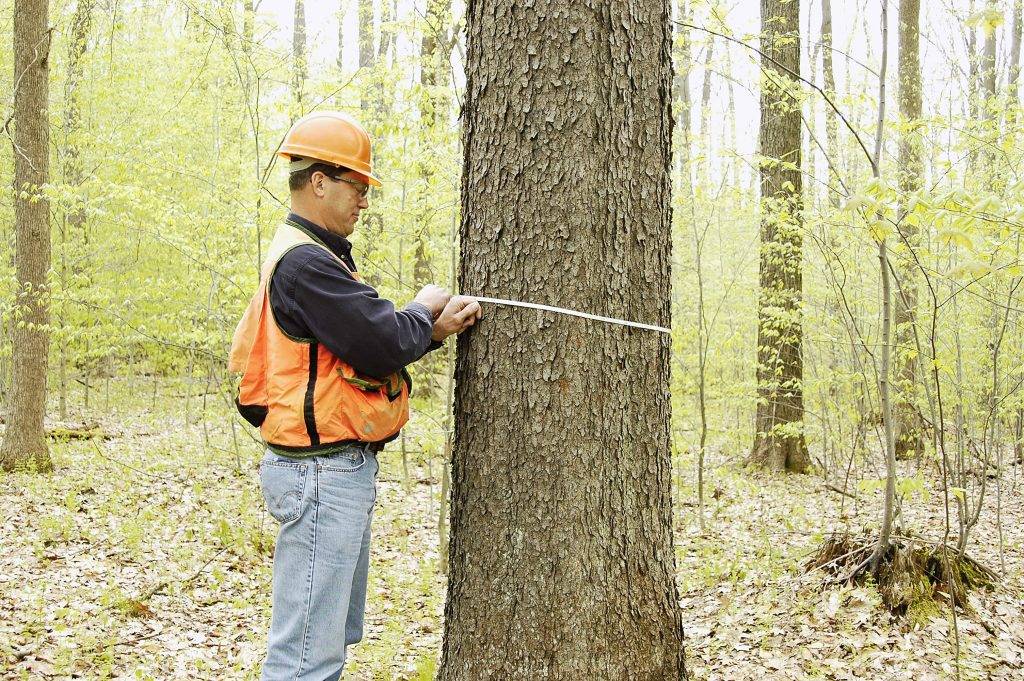

Chris is an industrial forester—a person who’s charged with managing and caring for trees, and who’s employed within the timber industry to do just that. He’s clear about the importance of his occupation in protecting natural resources.

“An industrial forester has the greatest impact on forests because they’re directly responsible for the harvesting of timber,” he explains.

Professional foresters are knowledgeable and experienced in forest management best practices as well as sustainable forest management. Chris’s team of industrial foresters is comprised entirely of professional foresters—those who hold undergraduate degrees in forest science. Their goal is to operate forest harvests in a way that promotes a continuous supply of high quality, desirable hardwood trees for the company’s sawmills, while maintaining and enhancing all the other benefits that healthy forest provide, such as clean water, clean air and recreation, both for today and for future generations.

The work of sustainable hardwoods forestry

For consumers of natural hardwoods products, the benefits of well-managed forests are clear.

“Because we operate in a way that promotes the sustainability of the forest,” Chris explains, “NWH can ensure that our timber is of high quality. Having high quality hardwoods as raw material produces valuable hardwood lumber for our customers. Our customers then use our lumber to create beautiful hardwood products.”

Chris was introduced to industrial forestry in high school while working maintenance at a summer camp with a large forested area. The camp was planning a timber harvest of the forest, and the forester invited Chris to tag along and watch their tagging and selection process. The encounter inspired Chris to obtain his Bachelor of Science in forest science from Pennsylvania State University.

Today, Chris oversees a team of 10 professional foresters at two sawmills in northwest Pennsylvania that manufacture FSC- and PEFC-certified hardwood lumber for cabinet makers, molding shops, furniture and flooring manufacturers.

He’s spent nearly 30 years as an industrial forester—first, in the Forestry Department of Industrial Timber & Lumber Company (ITL), and now, following NWH’s 2015 acquisition of ITL, with NWH.

In fact, the NWH acquisition of ITL added 11 foresters to the NWH forestry department. The company now has a team of 40 foresters that purchase timber for sawmills while focusing on sustainability and proper forest management.

A forest’s past shapes its future

“There’s a strong heritage of the timber industry in this area,” says Chris, who grew up in rural Pennsylvania.

Early settlers harvested pine, oak and maple for building settlements and then for the nation’s westward expansion. During the Civil War, hemlock bark became a major source of tannin for producing leather goods and the area’s pine and hardwoods were used to support the burgeoning coal industry’s mining tunnels. By the early 1900s, much of the area was heavily logged and depleted.

Following the creation of the National Forest Service and the establishment of national forests, forests began to regrow. Forest management practices since the beginning of the 20th century have focused on maintaining healthy, vigorous forests for environmental, recreational and economic purposes.

“The forest we have now resulted from those early harvests,” says Chris. “The mature trees that are currently being harvested are 80-120 years old. A lot of forest management has occurred in the last 10-20 years to regenerate these maturing stands of timber.”

Today, most of the timberland of northwest Pennsylvania is privately owned, but other significant timberland ownership includes state (PA State Forest Land), federal (Allegheny National Forest), and timber investment organizations (TIMOs, REITs). The area supports large areas of second-growth hardwoods forests which include species such as black cherry, red oak, red maple, sugar maple, ash, white oak and yellow poplar.

The quality of Pennsylvania cherry wood is known worldwide, but Chris won’t allow forestry practices to take the credit for the region’s most well-known hardwood. “It all has to do with the mix of sun, precipitation and soil,” says Chris. “The cherry here is so good because we have the perfect habitat here for the species.”

How industrial foresters ensure sustainability

Protecting the health and variety of the unique Pennsylvania forests is part of Chris’s job.

Because industrial foresters are involved in the actual timber harvest, their work impacts not only the trees, but also the soil, water and animal habitats where the harvest occurs. Timber harvests can dramatically affect the aesthetics of the area, as well as other forest users, such as hunters or birders, if they’re not managed with care.

Chris explains, “As industrial foresters, we protect the soil the trees grow in. We protect the trees still growing for the next generation. We protect water resources in the forest.”

“We want to make sure we don’t damage the trees that are supposed to stay, for example. We locate trails in the right place, so we don’t create steep roads that will erode. After harvest, we put in water control structures and regrade the road to stabilize the soils and protect the water.”

Timing of timber harvests also matters to Chris. In the winter, he explains, the ground is frozen. It’s not only easier to operate, but trees are dormant and there’s little damage to the ground. By contrast, spring is a dangerous time to harvest timber because the ground is loose and wet. Soil and roads can sustain more damage in those conditions.

Even transporting the logs out of the forest and to the sawmills factors into Chris’s sustainability planning. His foresters make sure they protect streams and water sources in the forest throughout the entire process. They look over the entire area and plan how to avoid intersecting water sources when removing logs on skid trails, minimizing the number of trails needed and the amount of disturbance.

“If we don’t harvest the timber in the proper way,” he says, “we can pollute the water and destroy the ability of the area to grow another tree in the future.”

Foresters always look ahead

Chris wants future generations to be able to enjoy and benefit from forests—and he also wants future generations to learn to care for them. For 20 years, he’s been going into schools to introduce elementary, middle and high school students to forest ecosystems, forest products and forestry—especially industrial forestry—as a career path.

“It takes a long, long time to grow trees. We, as foresters, are looking 100 years forward.”