Hardwood Timber Tipping Point

We’re Now Losing More to Mortality Than We Are Harvesting

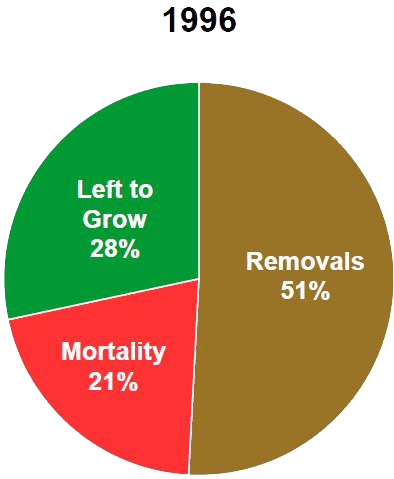

For decades the U.S. hardwood industry has proudly proclaimed that it harvests far less hardwood timber than is grown annually (even after discounting for natural mortality). That truth has been fundamental to our sustainability messaging, and should have validated to the public and politicians that our industry is a good steward of the forest resources. It did not. Or, at least, it did not motivate environmentally minded consumers to preferentially select solid hardwood products over substitutes and imports. And, as a result, Eastern U.S. hardwood harvesting declined 29% from 1996 to 2022, and has likely fallen significantly further over the last three years. At the 50-year peak in 1996, hardwood removals consumed 64% of the net annual growth, but removals fell to just 39% of net annual growth in 2022 (Figure 1). [All data presented herein are derived from the Forest Service’s 2022 Resource Planning Act (RPA) tables. On a technical note, in its comparisons with growth and mortality, the Forest Service reports growing stock “removals,” not harvests. Removals include anything that removes growing stock from timberland—including harvesting, land reclassification, urban expansion, and land development. Actual timber harvesting will, thus, be less than removals, though for simplicity, and under the assumption that harvests account for a majority of removals, we will use the terms interchangeably.]

From a forest health and vitality perspective, the decline in hardwood demand is increasingly devastating. Trees have limited lifespans and forests have carrying capacities. As trees age and those carrying capacities are reached, natural mortality increases. It takes active management to maintain younger, more vibrant forests, and it takes healthy markets to fund that active management. Even at a harvesting rate of 64% of net growth, hardwood forests were doomed to become overstocked and unhealthy eventually, but the sharply reduced harvesting rates of the last 30 years have accelerated that reality.

The Aging Forest

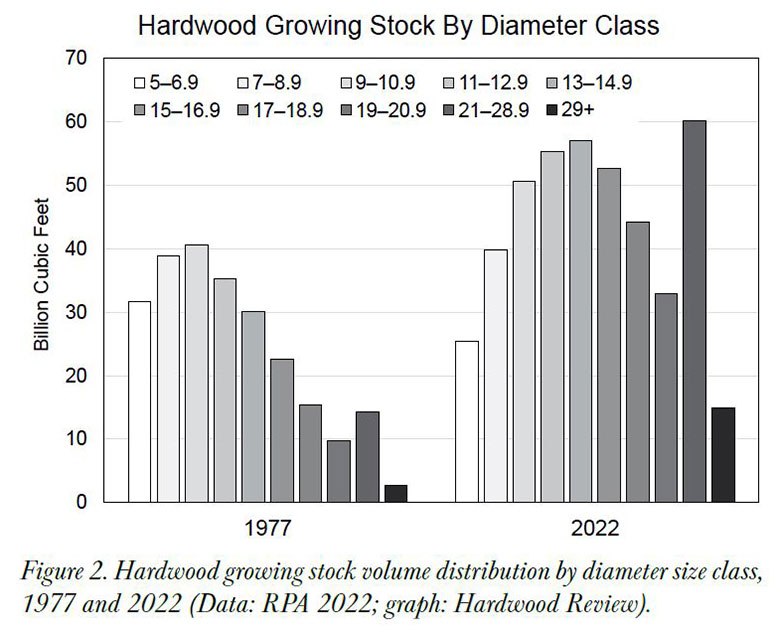

As we’ve detailed before, the impact of reduced harvesting on the health and composition of the forest is evident in Forest Service data. In our October 3 article last year (available to subscribers at HardwoodReview.com under “Past Feature Articles”), we chronicled the shift in hardwood forest composition from shade intolerant species like the Oaks to shade-tolerant species like the Maples. On a broader scale, that data show that the hardwood forest is aging. While we have more hardwood timber volume than at any time in at least the last 70 years—more probably in the last 125 years—it is increasingly concentrated in older, larger trees.

Note in Figure 2 that the peak volume of hardwood growing stock in 1977 was in the 9-10.9” diameter class. Forty-five years later, in 2022, peak volume had shifted to the 13-14.9” diameter class, and 17% of the total was in trees 21” in diameter and larger—up from 7% in 1977. As importantly, the percentage of hardwood growing stock in the 5-10.9” class—future sawlogs—shrank from 46% in 1977 to just 27% in 2022. The evidence indicates our forests are aging, and the increased mortality levels suggests forests are increasingly overmature and more susceptible to insects and disease. Further, the diameter distribution curves show that hardwood forests are not reproducing at levels necessary to sustain sawtimber size classes in perpetuity. All of this can be directly attributed to reductions in forest management and harvesting.

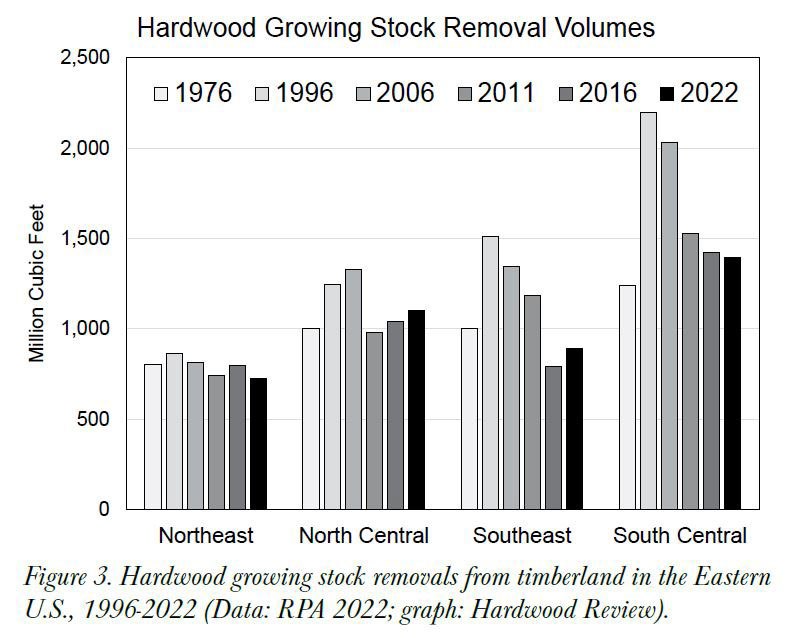

Reduced Harvesting

As would be expected given the market shift away from hardwood products and the fact that hardwood removals represent a much smaller percentage of net hardwood timber growth than in the past, timber harvesting is down substantially from the peak levels of the past 50 years, most notably in the South (Figure 3). While some of the disproportionate decline in the South could be related to declining demand for hardwood pulpwood, such reductions would also contribute to aging stands and overcrowding. Further, while total removals have declined relatively little in the two Northern subregions, 2022 removals accounted for just 23% of total growth in the Northeast and 27% in the North Central subregion—down from peak levels of 33% and 46%, respectively. In addition, due to the difference between “removals” and “harvesting,” actual hardwood harvesting in the North could be down more than indicated in Figure 3. While Southern cities have generally seen faster growth over the last several decades, Northeastern states remain among the most densely populated.

Figure 1. Percentage of total hardwood growing stock growth on timberland removed by harvesting, lost to mortality, and left to grow, 1996 and 2022 (Data: RPA 2022; graph: Hardwood Review).

The Tipping Point

For the first time in history—at least as far back as Forest Service data records—hardwood timber mortality exceeded removals in 2022. That is the end result of decades of falling demand for hardwood products, along with shifts in public opinion about forests, policy shifts away from production forestry, increased urban sprawl, and no doubt a host of other factors. While there are arguably wildlife and ecological benefits to downed and dying trees, we will die on the hill defending the fact that we as a nation should be utilizing more timber than is lost to mortality—for the health of the forest, the economy and our industry. And, we suspect even those without a stake in the industry would agree if they understood what is happening.

The clear message we should be communicating to consumers is that, not only are their choices for substitutionary products increasing greenhouse gas emissions, consuming finite petroleum resources, and costing American jobs, they are also degrading our forests. Based on the Forest Service evidence, that message can no longer be considered industry propaganda. Simply put, the long-term, environmentally driven shift away from wood products—exacerbated more recently by the price-driven market shift to imports and cheaper substitutes—is destroying the forests those consumers and policies sought to save. This may be one of the most devastating lessons in unintended consequences of our lifetimes—of which the average consumer is still blissfully ignorant. The only obvious solution would seem to be a shift in the American and global consumer ethos back to demanding products that actually benefit the forest. Though we’ve been making those arguments for decades, perhaps the forest has reached at tipping point at which some will begin to hear.

A Special Thanks

This article is reposted with permission from Dan Meyer at Hardwood Review — January 9, 2026.

Share This Post!

About NWH

Founded in 1967, NWH has established itself as a leading manufacturer and supplier of hardwood lumber across North America, Europe, and Asia. Committed to streamlining the customer experience, NWH services a variety of sectors including furniture, flooring, cabinet, molding, and millwork. Offering more than 14 hardwood species from the main U.S. growing regions, along with imported plywood and exotic lumber, NWH operates more than 30 manufacturing and warehousing facilities nationwide. The company is dedicated to sustainability, providing only high-quality, sustainable hardwoods to protect our resources today and for future generations.

For more information, please visit nwh.com.